Ben Rubin is no stranger to building digital neighborhoods. The tech entrepreneur first broke through in 2015 with Meerkat, an one-to-many livestreaming app that quickly hit millions of users before Twitter shut off the data it relied on. After sunsetting it in 2016, Rubin followed with Houseparty, a group-video-chat app he once described as a night-time version of Zoom. Before Epic Games acquired the app in 2019, friends used Houseparty to “drop in” on their digital conversations via video chat.

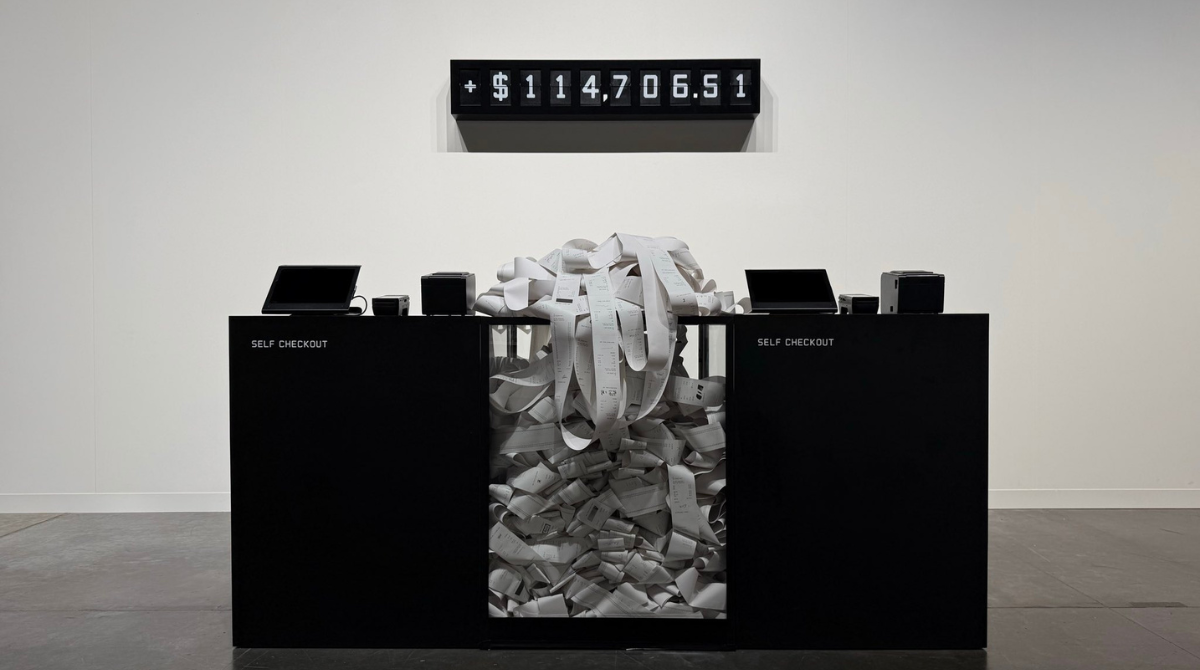

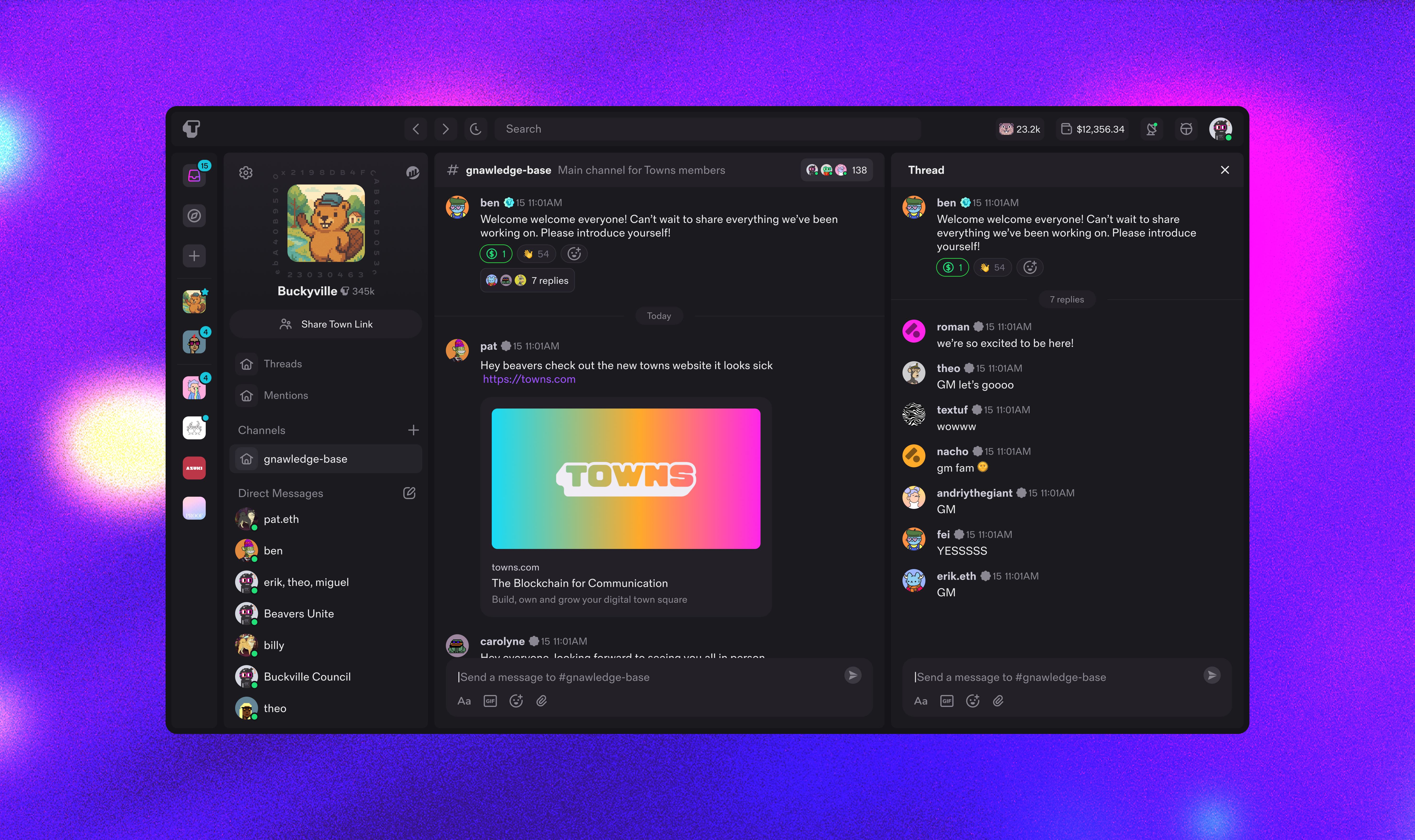

Now Rubin is behind Towns, a communication protocol designed to give communities control over their own spaces. He says the platform has logged more than $40 million in group-chat revenue since launching in October 2024, with an estimated 1.5 million users.

Instead of selling ads, Towns runs on subscriptions. Some group chats are free, others charge, and node operators stake a token to help run the network. Rubin believes this model makes it harder for bots to take over. “If a bot wants to exist in it, it will pay,” he said. “Whatever bot is there, it has to behave in a certain way and pay up.”

At its core, Rubin argues, social networks reflect one universal need: “Every social network is a dating app.” By that, he means people are seeking connection and recognition—and that Towns is built to sustain those exchanges without the distortions of the ad-driven feed.

Ahead, OpenSea speaks to Rubin about his path from viral apps to protocols, what people really want out of social media, and how Towns is trying to deliver it.

Note: This transcript was edited for length and clarity.

OpenSea: Your career can be described as one long pursuit of connection. You’ve built tools that help people gather in digital spaces. Before Towns, you created Meerkat and Houseparty, both of which had huge cultural moments. Can you walk me through each of these projects—what they did, how people used them, and how one led to the next?

Ben Rubin: Funny enough, I studied architecture in school. By the end of my third year, I decided I wanted to be an architect of digital spaces. Everyone was walking around with an internet-connected camera and a screen in their pocket, and I thought there was more opportunity to connect people that way than by building physical structures.

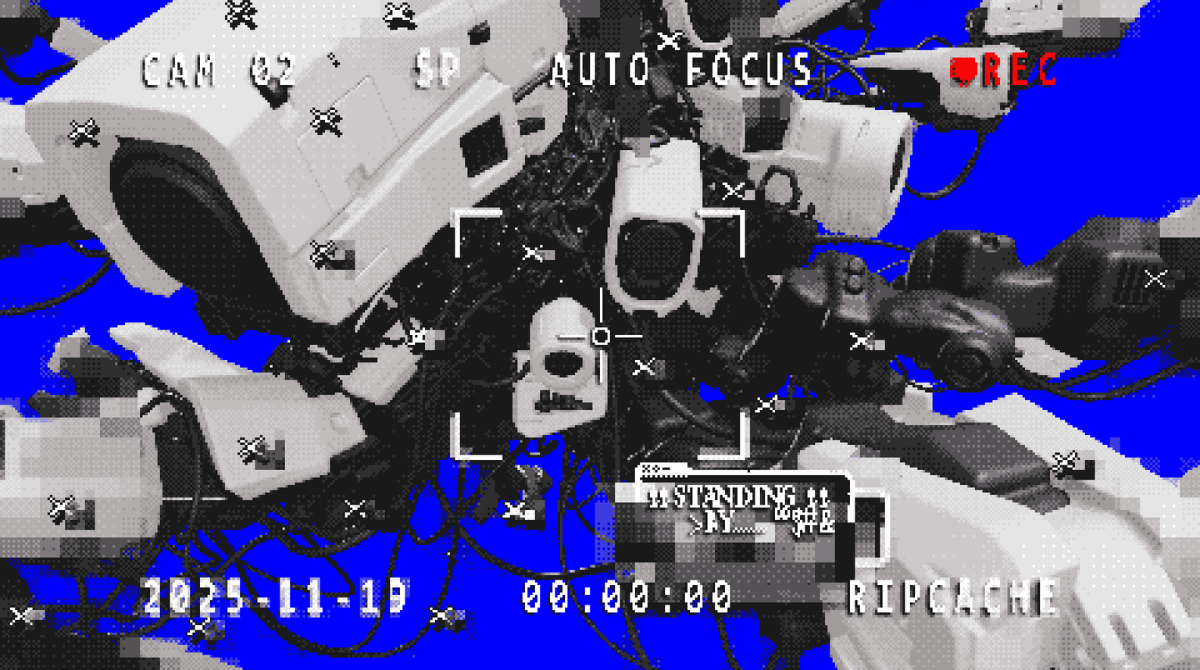

So I left school in 2012 to build my first startup, which focused on live streaming. After a few attempts, the first hit product was called Meerkat. It was a one-to-many live broadcasting app designed specifically for Twitter.

At the time, Twitter had a very robust developer API. Back then it was almost as permissionless as you could get. You still needed to authenticate, but you could access the graph data—usernames, relationships—and even take actions on a user’s behalf with their consent.

People were building all kinds of interesting Twitter clients because the API was so robust. We used that access to create a new kind of live streaming experience. You’d download the app, log in with one click, and from then on it was just one button to go live.

It worked because we built it directly on Twitter’s API. Immediately, you had your entire follower graph. It would post to your profile, and people scrolling their feed would see the live video. Just by clicking play, because they were already inside Twitter, you could see who else was watching. That dynamic created a massive wave of growth. Within two months, we went from zero to 20 million users.

OpenSea: And then what happened?

Ben Rubin: Twitter cut off the API access. It was during South by Southwest in 2015. They shut down the graph access, which basically killed our growth. They had actually bought another live video company long before we launched. They hadn’t released its product yet, but because they were worried about competition, they just turned off the API.

OpenSea: So you pivoted. Your next project, Houseparty, came out a year later. How did you approach the new project?

Ben Rubin: In late 2016, early 2017, we launched Houseparty. It was all about group video chat. The idea was to recreate the feeling of being at a friend’s house where people can casually drop in and out of conversations. If you and I are talking on Houseparty, and we’re friends, then your friends—even if I don’t know them—can join the conversation as long as you’re there.

OpenSea: It was like the digital equivalent of knocking on the door, popping your head in, and saying, “Hey!”

Ben Rubin: Well, less intrusive than showing up uninvited, but still natural. That kind of lightweight social mechanic took off. Millions of people used Houseparty, and we eventually sold it to Epic Games in 2019. It kept running into the pandemic, when video chat became a lifeline for a lot of people.

OpenSea: Looking back at both apps, what did you learn about what people actually value in online connection?

Ben Rubin: At the core, I think people are always trying to feel desired and to find real connection. That’s true across every social platform. Take Facebook: the reason it took off early on is because you could suddenly see real identities, real photo albums, and get a window into people you might have a crush on. Then layers of abstraction came in—the feed, likes, reactions—but underneath it all, it was still about attraction and intimacy.

The same is true for Snapchat. People said disappearing photos were stupid, but in reality it was about expressing yourself in a way that felt safe, less permanent, and less judged. And yes, that is often linked back to dating.

I think every social network is essentially a dating app. Maybe not explicitly, but the mechanics are built around the same human desire to be seen, understood, and wanted.

OpenSea: You’ve called Towns an “ownable communication protocol.” What does that actually mean, and why was web3 the right place for it?

Ben Rubin: Building the Towns app on the Towns protocol has allowed us to take away the mediator. On web2 platforms, you don’t really have incentive alignment. The platform is trying to get more eyeballs for longer stretches of time so it can sell ads. Beyond that, the platform is motivated to augment the kind of news you see, because it quickly figures out what will keep you scrolling.

So what Towns is doing is asking: if the conversation has value, how do we make sure people can find it and allocate capital toward it? We align incentives between the protocol, the people having the conversation, and the people engaging with it. Everyone gets a share of what users are willing to pay.

Here, the default is simple: if it’s valuable, people will pay. If it’s not, they won’t. Part of those fees go to the protocol to cover operations. There are no ads, no algorithms manipulating your feed, and it becomes too costly for bots to thrive.

OpenSea: So you’ve built something that makes it expensive—even irrational—for bots to operate?

Ben Rubin: It’s not that Towns disincentivizes bots; it’s that if a bot wants to exist here, it has to pay. And if it’s paying while doing bad things, it’s still contributing to the stakeholders. To survive, a bot needs to be a net giver. Otherwise, it doesn’t make sense for it to operate.

OpenSea: How have things been going so far?

Ben Rubin: Well, we launched last October, and since then group chats on Towns have generated more than $40 million in revenue. Last month, we also launched $TOWNS, the protocol’s utility token. Node operators stake that token to run the network, and they’re rewarded on an inflation schedule that’s offset by subscription fees from people joining private group chats. The idea is to make the whole thing sustainable, without ads or extraction.

OpenSea: How many users are on the platform?

Ben Rubin: About 1.5 million.

OpenSea: And what kinds of group chats are driving that growth?

Ben Rubin: There are some experimental ones—anime, gaming. But the majority right now are traders: alpha towns, memecoin towns, that sort of thing. It’s a bit like Snapchat’s early days. Memecoins are fun, maybe fleeting, but they draw people in. Over time, you hope use cases expand into deeper territory.

OpenSea: If Towns continues to grow in popularity, how do you think it will change the way communities gather online over the next five years?

Ben Rubin: I’ve learned not to predict exactly where things will go. My focus is setting it up for success every day—making sure it’s sustainable, fully owned by its community, and valuable enough that people want to support it.

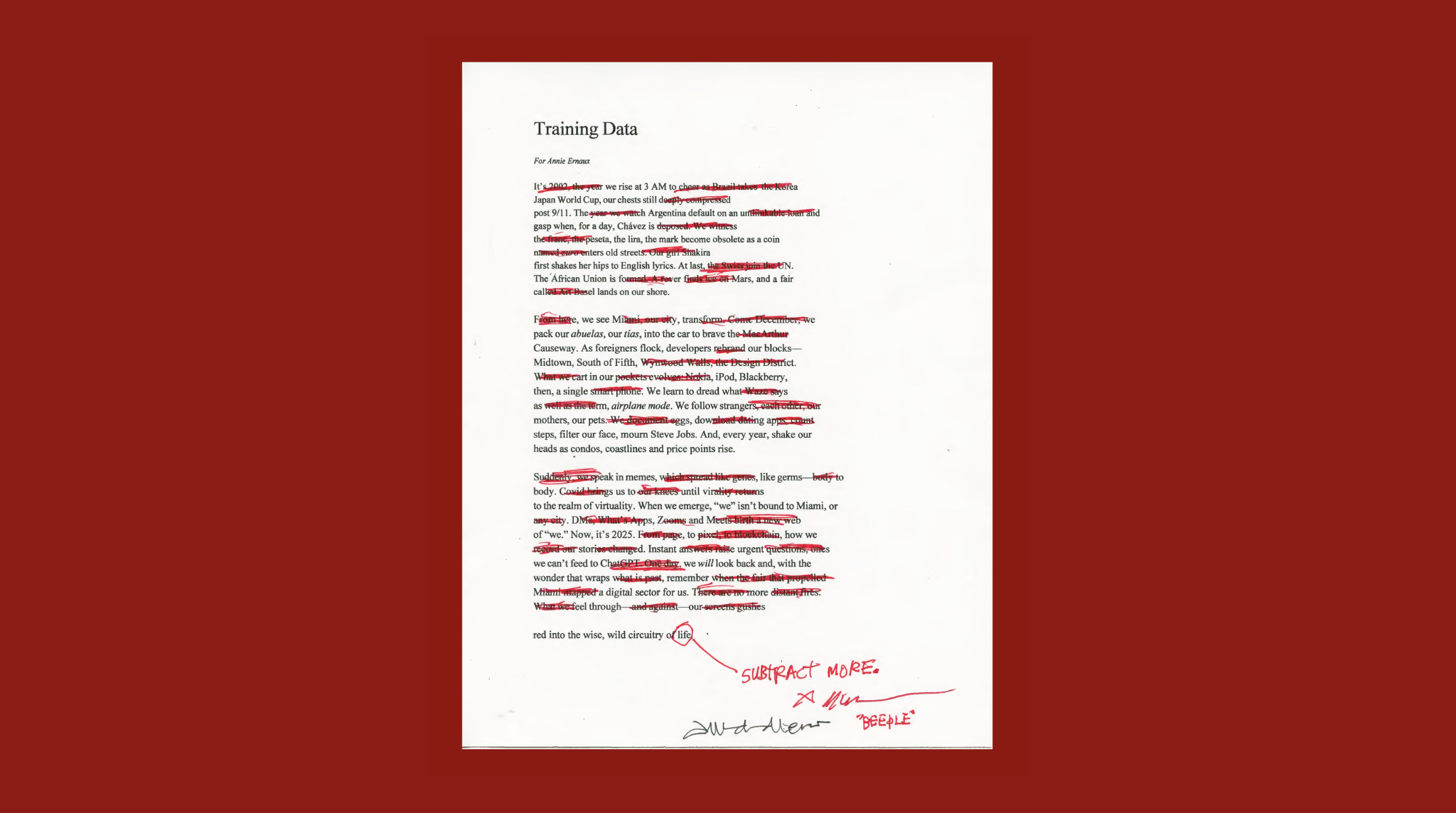

Most conversations that drive value online don’t benefit the people creating them. In a world of AI, the human insights—the lived experiences, the nuance—that’s the real alpha. That’s why real writers like you matter. AI can summarize steps, but it can’t replace emotional narrative.

Our job with Towns is to build a protocol that protects that kind of human value, allocates both capital and reputation fairly, and keeps it safe from invisible hands. If we can do that, the protocol can sustain itself and grow wherever communities take it.

OpenSea: And for someone new who wants to try it?

Ben Rubin: Just go to Towns.com, click “Open App,” and either join an existing town or create your own. All you need is an email address. The crypto side is abstracted away—even your mom or your neighbor can start a town. Some are free, some charge subscriptions, but there’s no cost to start one.

OpenSea: Ben, thank you so much for your time.

Ben Rubin: Thank you. I enjoyed it.

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)