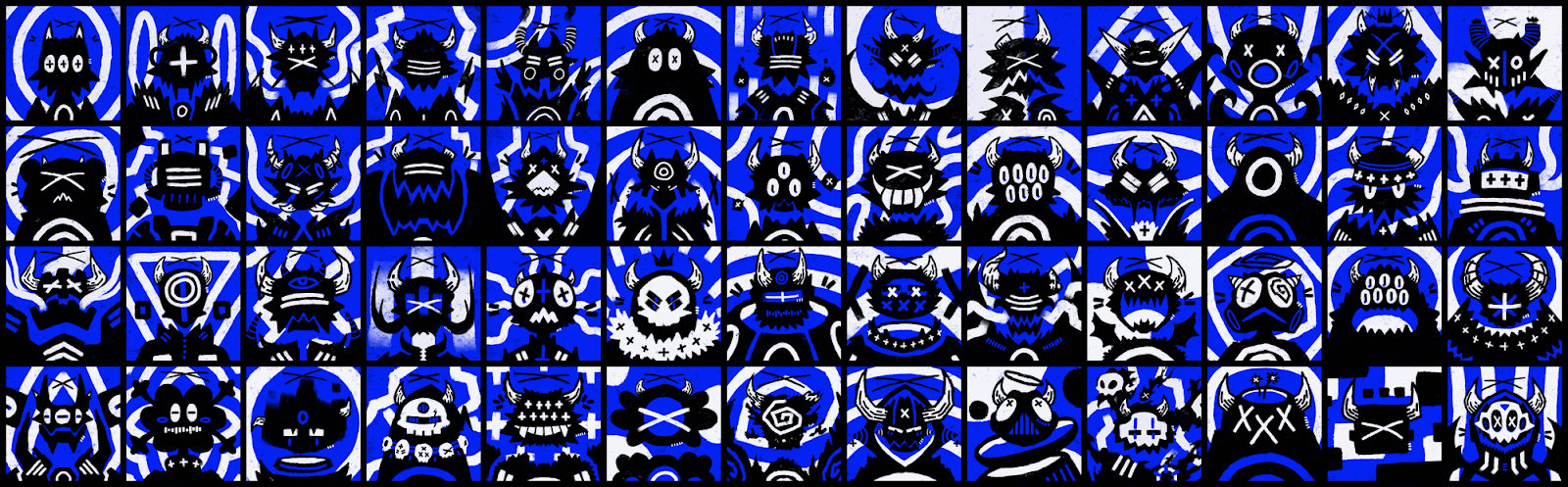

Des Lucréce creates art that lives in the in-between — between cultures, identities, and emotional states. Known for their signature Des Monsters series, Des explores themes of belonging, desire, and cultural displacement through bold, symbolic characters that act as both shields and mirrors.

In this conversation, we talk about how Des’ experience growing up across cultures shaped their creative voice, why monsters became central to their visual language, and how grief, theory, and digital storytelling weave into their work.

With their upcoming immersive exhibition The Erosion of Time set to open at the Museum of Art + Light, Des is expanding the world of Des Monsters — inviting audiences to engage with the collection in new ways and confront the contradictions these creatures carry.

OpenSea: You’ve described yourself as existing in a “No Home Center” — a limbo of living between cultures. How has that sense of in-betweenness shaped both your identity and your creative voice? Were there formative experiences, either in Norway or the U.S., that crystallized this feeling for you?

Des Lucréce: One of my earliest memories of this feeling was during a trip to Vietnam when I was around seven. Every time we stepped into the street, people would stop and stare. I kept hearing them whisper "Việt kiều” — a word I didn’t know at the time. When I asked my mom what it meant, she gently told me, “It just means they know we’re not from here.” That stayed with me. Because we were Vietnamese — by blood, by language, by lineage. And yet, even there, I was foreign. "Việt kiều” directly translates to “overseas Vietnamese” carrying a literal meaning but also a cultural meaning of being foreign even within Vietnam.

That was just one side of the equation. I was born in Norway, raised in the US, and in both places I was made to feel like I didn’t quite belong either. The kids in school reminded me daily that I was different. The result is what I now call “No Home Center” — a condition of existing between identities, cultures, and expectations. It’s not just disorienting — it’s foundational. And it’s become the lens through which I make all my work.

This in-betweenness shapes everything: the characters I draw, the systems I critique, the emotional contradictions I try to hold in my works. My art isn’t about resolving that tension — it’s about dwelling in it. Giving shape to the parts of identity that are fluid, fractured, or too complex to categorize. For those of us who’ve grown up in the cultural margins, that limbo is our center — and I’m trying to build visual language around that truth.

OpenSea: Your creatures and monsters have become such a signature part of your visual language. How did they first emerge?

Des Lucréce: Monsters first emerged from a place of reactionary defense — originally as a way to visualize the hate I saw online directed at people like my mother during the pandemic. But over time, they evolved. They became not just representations of others, but also masks, shields, and eventually mirrors. They’re a language of exaggeration and distortion that helps me talk about identity, fear, and otherness in ways that feel both personal and collective.

OpenSea: With influences ranging from Jean-Michel Basquiat to Maki Haku, how do their styles or philosophies guide your creative process?

Des Lucréce: Basquiat taught me that rawness and chaos could be poetic. Maki Haku showed me the power of gesture and control within tight boundaries. Their work couldn’t be more different formally, but philosophically, they both deal with fractured identity and reclaiming language through mark-making. That’s what I carry into my process — letting form follow feeling, while making sure every line carries intentionality and tension. I was traditionally trained as a designer where form follows function, and this is something I’ve adapted to my current creative practice.

OpenSea: Much of your work explores themes like desire, identity, and pursuit of fulfillment. What draws you to these concepts, and what are you trying to reveal about the human condition through them?

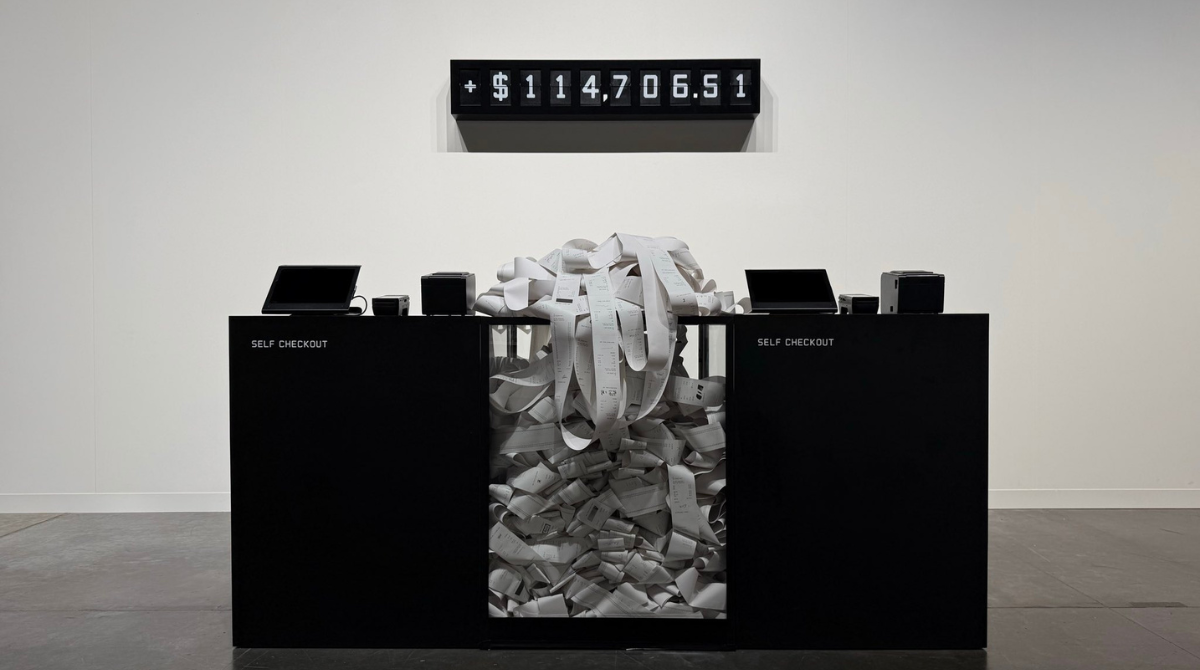

Des Lucréce: Desire, for me, is the engine behind everything I do — especially the kind we don’t fully understand. I was first introduced to Lacan’s idea of the objet petit a in school, and it’s stayed with me ever since. We’re always chasing things — success, recognition, belonging — thinking they’ll finally complete us, only to realize the chase itself is often more real, more intoxicating, than the destination.

My work isn’t about offering answers; it’s about holding up a mirror and asking: What are you really after? Is the value of a piece in what it is — or in how it was acquired? Does a burn increase meaning or erase it? Does collecting complete the self, or does it just reveal the gap we’re always trying to fill? These are questions I ask not just in the work, but of myself.

A small detail: for years, my web bios included the line “Life is about chasing Coke Zero™” — a direct nod to Žižek’s reading of Diet Coke as pure, unattainable desire. That tension — between the substance and the idea of the thing — runs through my entire practice. Whether I’m building game-theory-driven collections or reflecting on personal loss, I’m interested in the emotional and economic systems we build around wanting. Critical theory gives the work structure, but the beating heart is always that same question: What are we willing to sacrifice to feel whole? And what happens when even that doesn’t satisfy?

OpenSea: You’ve described your work as a quiet inquiry into longing and belonging. Are there particular questions or themes you find yourself circling back to in your creative practice?

Des Lucréce: There are themes I orbit again and again: longing, belonging, identity, distance. I return to these not out of habit, but because I still don’t fully understand them. The work is a quiet inquiry — a way to hold grief, desire, memory, and contradiction all in three animated frames. If anything, I think I’m always circling the question: What do we become when the places we come from don’t recognize us?

OpenSea: “Des Monsters” began as a response to the hate your family and community received during the pandemic, but it’s since evolved into a much broader bestiary. How has the emotional tone of the series shifted over time — and do you see these monsters as projections of others, or reflections of yourself?

Des Lucréce: At first, Des Monsters were reactive — portraits of hate, like mugshots or wanted posters. They were raw, charged, and deeply personal. I was responding to the surge of anti-Asian sentiment I saw during the pandemic, especially the anonymous vitriol directed at people like my mother, who ran a nail salon in the rural South. These early works were about giving form to that ugliness, about identifying it, naming it, and putting it on display.

But as the series grew, something shifted. The monsters began to soften — not visually, but emotionally. They became more symbolic, more archetypal. I realized they weren’t just projections of aggressors; they also embodied survivors, bystanders… and eventually, parts of myself. The roles we play in systems of harm and healing aren’t always cleanly divided. Over time, I came to understand the monsters as reflections of the stories I’ve lived through, and the roles I’ve played in them — willingly or not.

Something I didn’t expect was how my collectors responded. Many started using their Monsters as profile pictures. It became this quiet but powerful form of identification, of solidarity. Some of these pieces have been with their holders since 2021, and over the years I’ve built relationships with both the collectors and the monsters they chose. In that way, the project became a kind of therapeutic loop. The same images that started as confrontational began to feel disarming — even redemptive. It reframed what I thought I was doing.

I don’t think I can pinpoint exactly how it changed me, but I know my newer works feel lighter. There’s more air in them. Maybe the tone has softened not because the world is less hostile, but because I’ve spent more time learning how to hold complexity without letting it calcify. Des Monsters started as a scream — but now, it’s more of an echo chamber, filled with stories, contradictions, and the quiet relief of being seen.

OpenSea: What kind of conversations has the series sparked with your audience – especially among those who also feel culturally or emotionally displaced?

Des Lucréce: The most meaningful conversations have come from people who see themselves in the Monsters — not just aesthetically, but emotionally. I’ve had messages from collectors who’ve felt pushed to the margins of their communities, saying that something about the Monsters made them feel seen.

These aren’t just illustrations — they’re avatars of contradiction: fear, survival, cultural tension, resilience. Some people view them as projections of aggressors; others recognize them as internal shadows. But more and more, I hear from people who realize they’ve been the Monster. That emotional displacement — feeling like a foreigner in your own body, in your own country, in your own culture — is a recurring thread.

Those responses have shown me that what started as a personal confrontation with hate has grown into a kind of shared archive. A bestiary for those of us who’ve lived between worlds, and needed a form to hold that in-between space. That kind of resonance is more than I ever expected, and it’s why I keep it the center of the world I’m building.

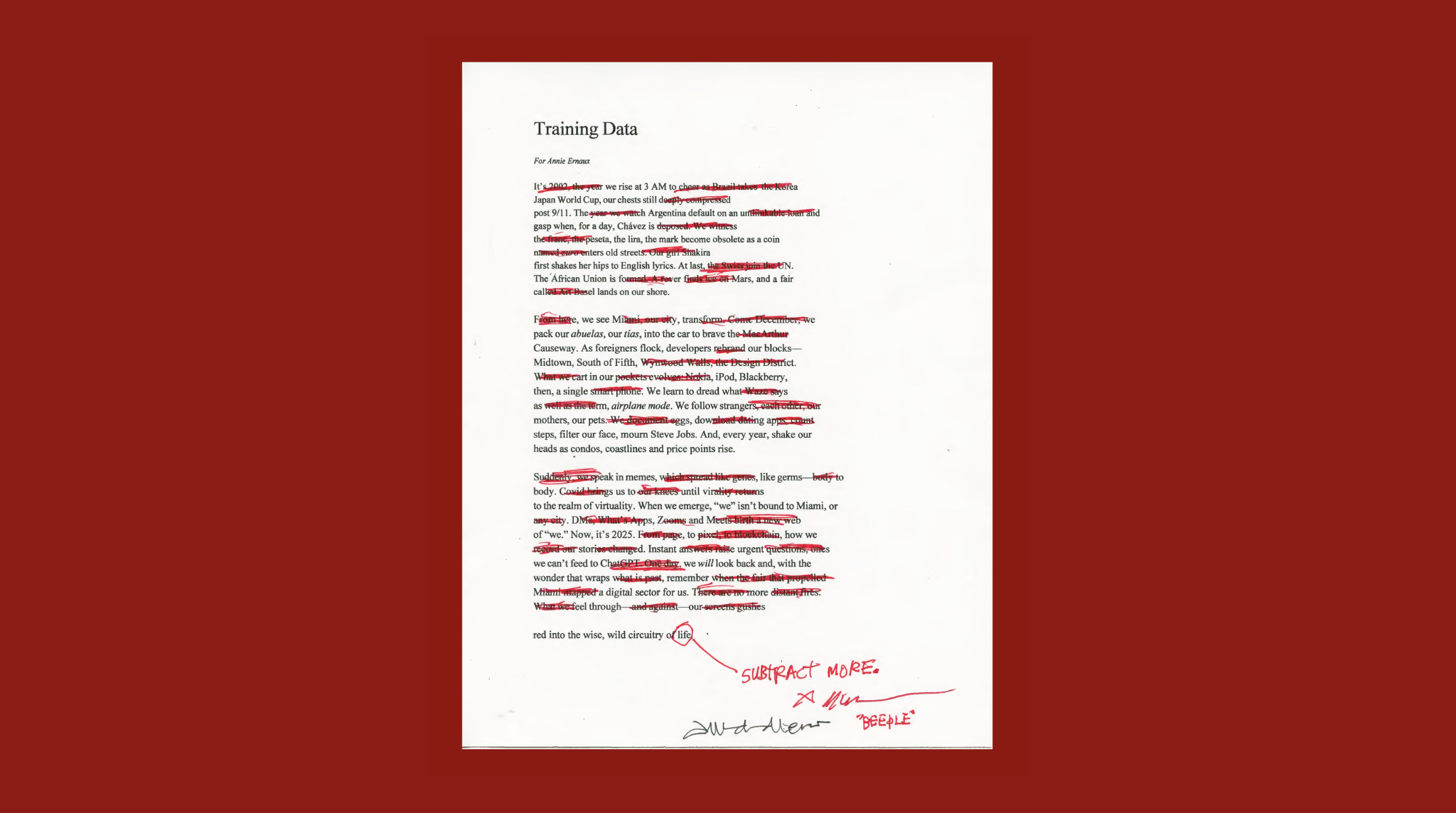

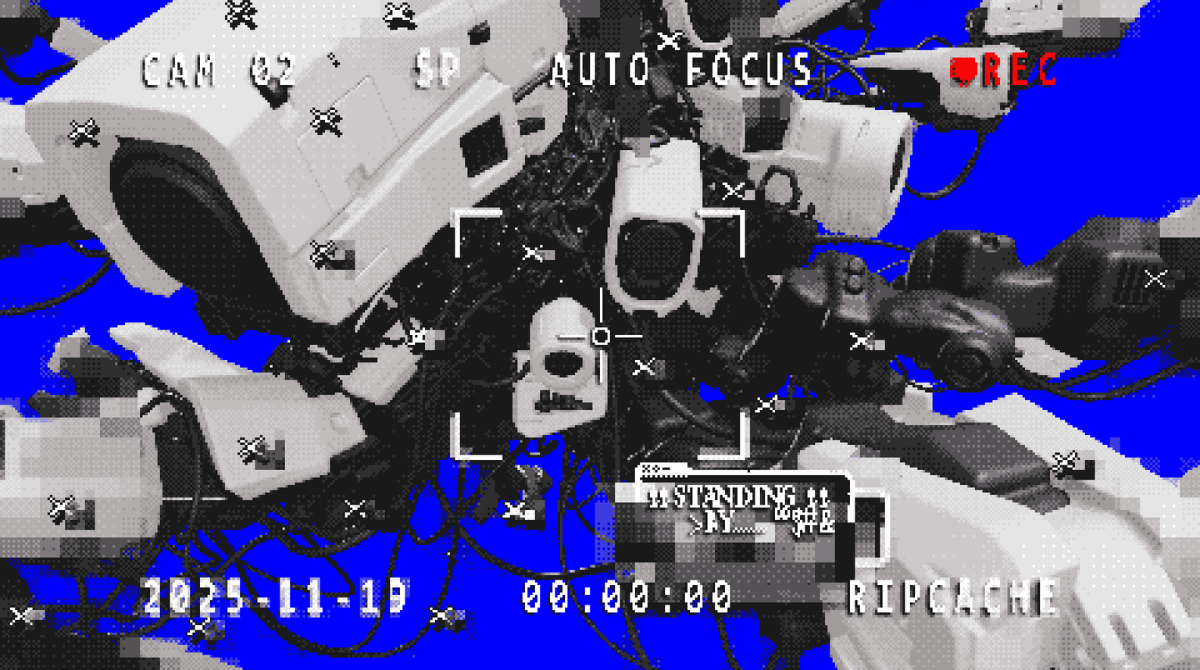

OpenSea: Your use of digital tools as a means to explore how technology and connectivity shape our sense of self. How do you see technology shaping who we are today, and how do you explore that in your art?

Des Lucréce: Technology has fundamentally shifted how we construct and project identity. In digital spaces, we’re constantly building personas — curated, exaggerated, sometimes anonymized versions of ourselves that allow us to feel empowered, protected, or even seen in ways we might not in real life. I find that tension fascinating: is anonymity a mask, or is it actually a kind of truth?

That question sits at the heart of Des Monsters. Avatars of what people become when identity is unmoored from consequence, but also when it’s liberated from social constraint. The same tools that allow cruelty also allow creativity, survival, and new forms of expression. I think some of the most honest things people say come from behind anonymous accounts.

So I use digital tools not just to make the work, but to engage with these systems critically. The language of PFPs, gamified collecting, and profile-based identities all play into how the Monsters are framed. They're hyper-personal, but designed to live in a networked world where identity is fluid, commodified, and increasingly fractured. The work is as much about how we present ourselves online as it is about who we are when no one’s watching.

OpenSea: You’ve turned to art to process difficult emotions, including grief after the loss of your father. How did that experience influence your creative approach, and how do you navigate making work that’s deeply personal?

Des Lucréce: Losing my father reshaped everything. I hadn’t spoken to him in nearly 18 years when I got the call — he was dying in a hospital bed back in Norway. I saw him over FaceTime for the first time in nearly two decades. Five days later, he was gone.

I had always imagined reconnecting with him once I "made it” — once I could show him I had built something of myself. That dream was gone overnight, and I was left with all the conversations we never had, all the milestones we’d never share. That kind of grief doesn’t announce itself —it just shows up and asks if you’re ready. And you never are.

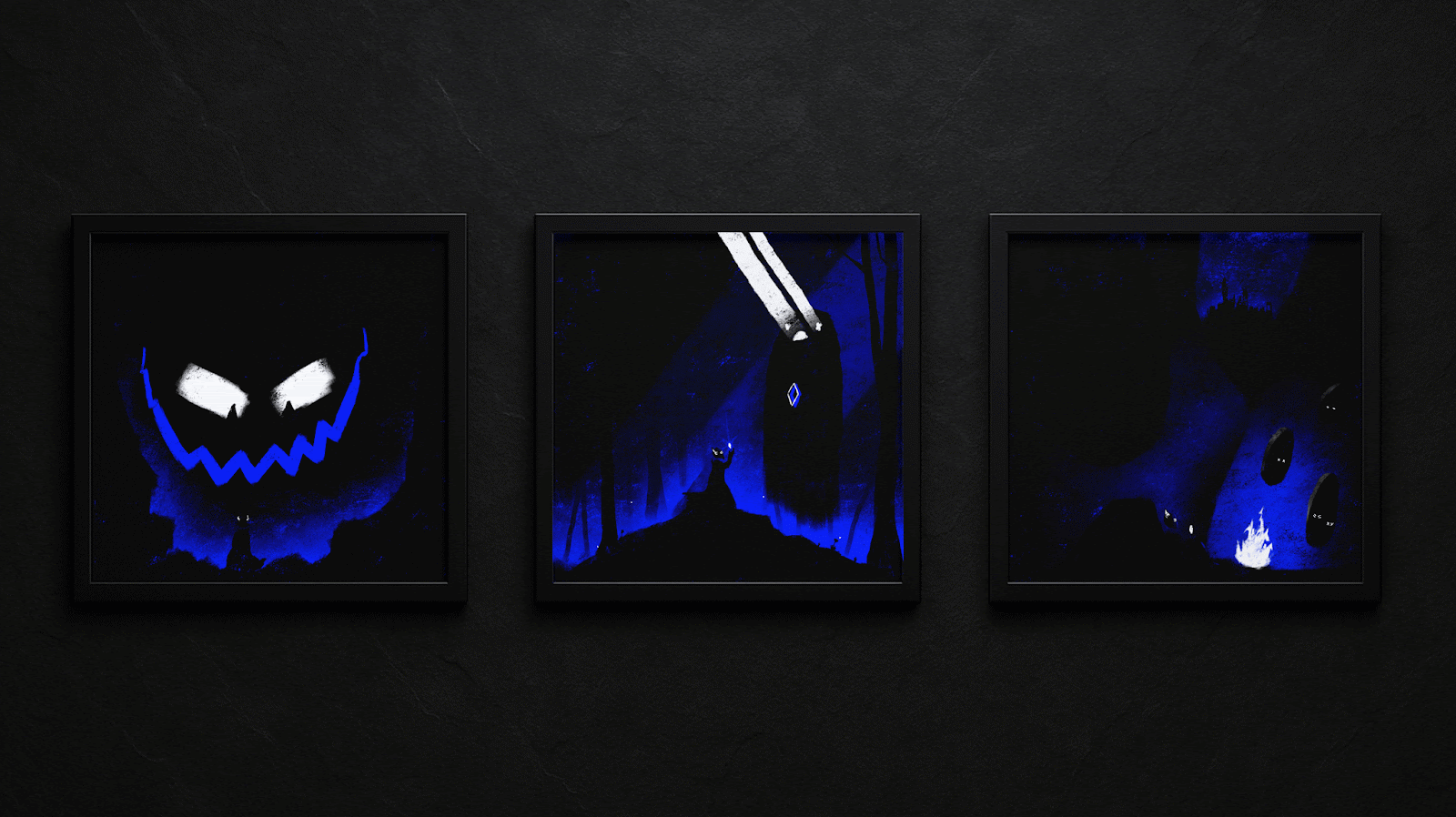

A New Journey, consisting of The Encounter, The Discovery, and The Night, came out of that loss. It was me trying to make sense of what success means when the people you wanted to share it with are no longer here. It was the first time I made work that felt more like a conversation with the past than a projection into the future. It didn’t need to be clever or marketable — it just needed to be honest.

Since then, I've come to realize that grief isn’t something you resolve — it’s something you integrate. It leaks into your practice, not as a theme, but as a lens. It’s in the pacing, the symbolism, the negative space. And making personal work doesn’t mean oversharing; it means honoring what needs to be said even if it’s said quietly.

I’ve also learned to give time to the pieces that feel unresolved. Not everything needs to be published, not everything needs to land. Some works just need to exist for me first. That’s been a big shift. The pressure of performance is always there in public-facing art, especially in web3. But when something truly personal emerges, I try to let it speak before I think about how it might be received.

Ultimately, I think grief gave me permission to slow down. To not just produce, but to reflect. And in that space, I’ve found a different kind of clarity — not clean, not resolved, but honest. And that’s where the real work lives.

OpenSea: Is there a medium, project, or collaboration you haven’t explored yet but feel drawn to in the future.

Des Lucréce: Absolutely. A bit of a shameless plug: My upcoming show The Erosion of Time, opening September 6, 2025 at the Museum of Art + Light, marks a turning point in how I think about my work as an immersive experience, collaboration, and how the Monsters live in the world. Co-presented with Dean Mitchell, the exhibition spans 3,500 sq ft and transforms the walls and floor into a multi-sensory environment where light, sound, motion, and myth converge. Working with MoA+L’s team, I'm pushing digital storytelling to magnify emotional resonance and cultural memory — the past stretched across walls and the imagination.

This show has made me rethink the scale and reach of my work. I’ve started to imagine Monsters not just on screen or canvas, but fully embodied — integrated into spatial installations, merchandise, and even visitor-activated encounters. This possibility of expanding from digital collectible to physical presence — streetwear, posters, plushies — feels like a natural next chapter, and it challenges how art, identity, and ownership intersect across media and markets.

In essence, I want to break out of the frame (both literally and conceptually) and let the Monsters — and the questions they carry — live in unexpected places. With The Erosion of Time, I’m testing that boundary, and I’m excited for how these figures will continue to evolve alongside the systems and communities that engage with them.

The show will be open for 9 months, so if you ever find yourself in Manhattan, Kansas — please stop by!

OpenSea: Thanks, Des!

Des Lucréce: Thank you for this wonderful conversation! I hope my Monsters find you and everyone reading well.

.png)

.avif)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)